Higher Education and Research in France, Facts and Figures - Summary

Like the previous editions, the 9th edition of Higher Education and Research in France, Facts and Figures presents an annual overview, backed up by figures, of developments within the French system, its resources and outcomes. Wherever the data permit, an international comparison is provided. A double page is devoted to each theme (50 in total), including a summary of the main data available and several graphs and tables as illustrations. This publication relies on key national and international statistical sources providing data on higher education and research in France.

2014, stabilisation of expenditure on higher education after a long period of high growth

In 2014, the French nation spent €29.2 billion on higher education, an increase of 0.3% in comparison with 2013 (at constant prices, i.e. adjusted for inflation). Expenditure on higher education has more than doubled since 1980 (by a factor of 2.6, at constant prices), increasing by an average of 2.8% a year. In 2014, average expenditure per student in higher education totalled €11,560, 40% more than in 1980.

It was equivalent to the average spending for a student in a general or technical secondary school (€11,060 in 2014). However, the cost per student varied between different types of courses, ranging from €10,800 per year on average for students at State-run universities to €14,980 for those attending classes preparing for admission to Grandes Écoles (CPGE). This variation is explained in large part by the level of educational supervision provided.

Staffing costs accounted for more than two thirds of expenditure on higher education. At the start of the 2014-15 academic year, the teaching and research potential in public higher education institutions under the responsibility of the Ministry of Education, Higher Education and Research (MENESR) was 91,000 teachers, which included 57,000 teacher-researchers and equivalent, or GC1115~62%~GC1115 of all staff. Secondary teachers working in higher education and non-tenured teachers represented 14% and 23% of the teaching workforce respectively. The number of teachers working in higher education has increased by nearly 5% in ten years.

The French government provides the majority of funding for higher education, accounting for around 70% of financing in 2014, while households contributed just under 9%. At the start of the 2014-15 academic year, 680,000 students benefited from direct financial aid in the form of grants or loans. Financial and social support for students, including accommodation subsidies and forms of tax relief, totalled €6.0 billion.

In 2012, France devoted 1.4% of its GDP to higher education, leaving it one tenth of a percentage point below the average for OECD countries (1.5%) and far behind the United States (2.8%), Canada (2.5%) and South Korea (2.3%).

Student numbers at record levels

618,850 of the candidates who sat examinations in 2015 were awarded a baccalauréat, equivalent to a pass rate of 87.9%. The proportion of people in a generation that hold a baccalauréat was over 60% in 1995 and rose to 77.2% in 2015.

Almost all of those with general baccalauréats and 75.4% of those with technological baccalauréats were enrolled on higher education courses at the start of the 2014-15 academic year. Most of those with vocational baccalauréats went straight into employment, so the proportion of this group enrolling in higher education was lower. However, it has nonetheless risen sharply in ten years (to 35.1% in 2014, as compared with 17.1% in 2000, excluding work-study programmes). Nearly 75% of those who obtained a baccalauréat (of any kind) in 2014 went on to enrol on higher education courses immediately (excluding work-study programmes). A significant number, particularly among those with vocational baccalauréats, also continued on to higher education via work-study programmes.

Given the proportion of an age group that is now obtaining a baccalauréat, and the percentage that are continuing secondary education, it follows that nearly 60% of young people are now accessing higher education.

The Post-Bac Admission system centralises higher education course choices. In 2014-15, nearly 740,000 young people, mainly those studying in the final year of secondary school ('Terminale') submitted at least one course preference (6.5 preferences submitted on average). 60% of general baccalauréat holders, 50% of technological baccalauréat holders and 36% of vocational baccalauréat holders received an offer matching their first choice. One in three holders of the three main series of baccalauréat (general, technological and vocational) received their first choice when applying for selective courses, if we concentrate on the most representative of these. 35% of general baccalauréat holders wanting to enter classes preparing for admission to Grandes Écoles (CPGE) therefore received their first choice. The proportion was the same for technological baccalauréat holders wanting to enter a University Technology Institute (IUT) and nearly equivalent for vocational baccalauréat holders requesting admission to an Advanced Technician's Section (STS) (32%).

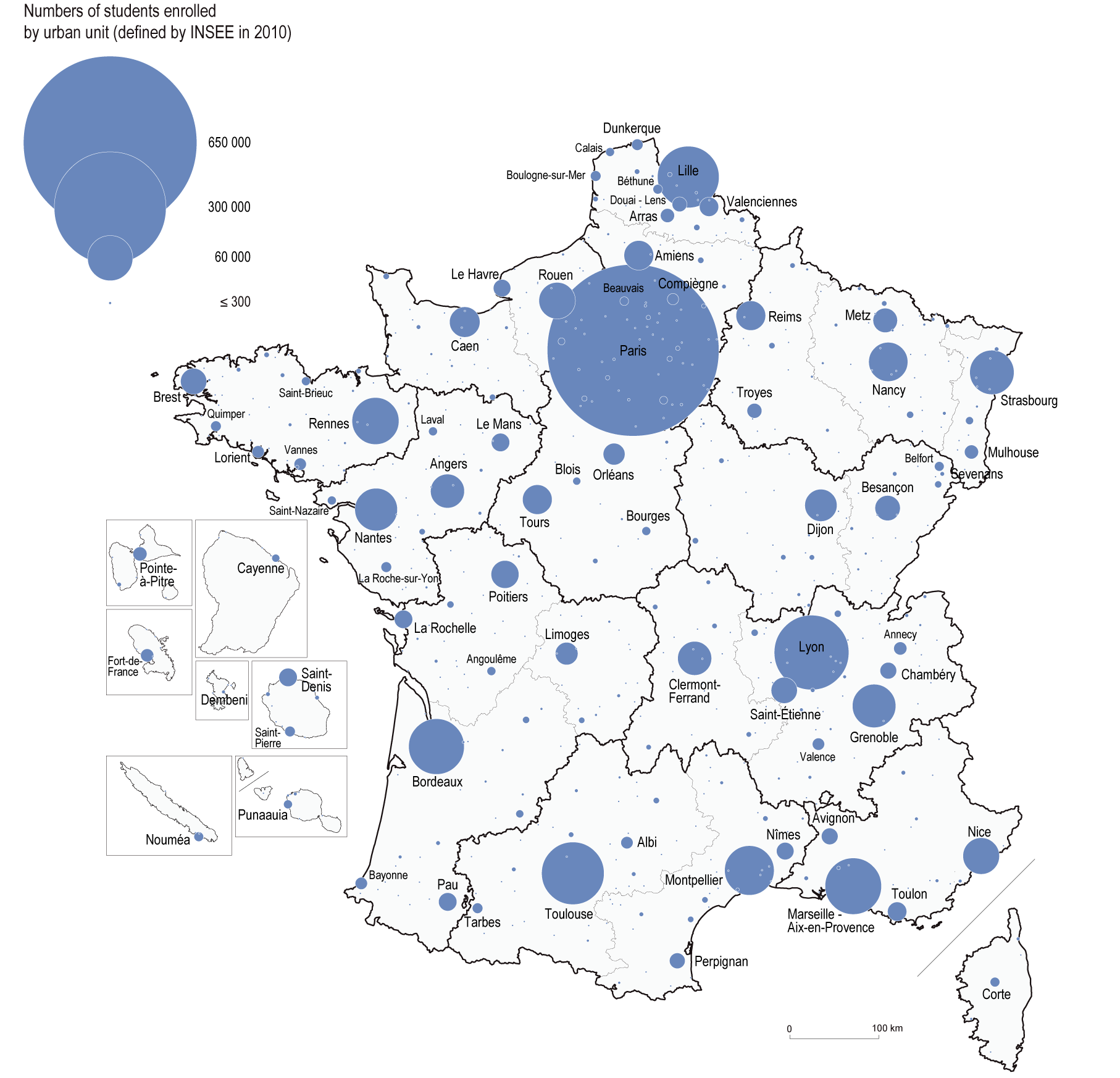

At the start of the 2014-15 academic year, 2,470,700 students were enrolled in higher education. This represents an increase of 1.7% on the previous academic year, meaning that the number of students has never been so high. This is explained by the fact that higher education in France now holds greater appeal for both young French nationals with baccalauréats and foreign students (who accounted for more than 12.1% of students in 2014). Since the early 2000s, private higher education institutions have seen the highest increase in student numbers (+ 58% between 2000 and 2014).

The overwhelming majority of those with general baccalauréats go on to university, many of whom enrol on general or healthcare courses. The most popular choices other than university programmes are vocational short courses at University Technology Institutes (IUT) or Advanced Technician's Sections (STS) and CPGEs.

The appeal of university education varies significantly between different disciplines. In the ten years between 2004 and 2014, the number of students enrolling on Healthcare courses has risen sharply (+ 31.9%). Law courses have also seen a sharp increase (+ 19.3%). In scientific subjects and physical education and sports science and techniques (STAPS) numbers have increased by 5.4%, having been in decline over the past decade. The number of students in the Arts and Human and Social Sciences, which together account for more than half of all students enrolled at university on general courses, fell slightly between 2004 and 2014 (- 1.9%).

Work-study programmes were first introduced in 1987 and were expanded as part of reforms to the French higher education system (‘LMD reform’) in 2002, consequently becoming much more widespread in higher education. The number of apprentices increased by 95% between 2005 and 2013. The increase in apprenticeships was only 2% compared to 2012, but has experienced an average annual growth rate of around 10% since 2005. The number reached 138,000 in 2013, accounting for 5.5% of all students in higher education. Nearly half of all apprentices were working towards a higher technical certificate (BTS), while one in ten were preparing for an engineering diploma or Bachelor’s degree.

PhDs are the most advanced qualification awarded by higher education institutions and doctoral research contracts provide many PhD students with their first professional experience. PhD graduates are a key driving force behind research in France. Training through research has been provided by graduate schools since 2000. 41% of theses are completed in less than 3 years. Nearly 14,400 PhDs were awarded in 2014. The number of PhDs awarded increased by nearly 6.5% between 2010 and 2012, but fell by 2.5% between 2012 and 2014. Most of the PhDs awarded (around 60%) were in scientific subjects. At the start of the 2014-15 academic year, there were nearly 75,600 PhD students, including over 40% foreign students. This population has been gradually diminishing since 2010.

Variations in pass rates between different types of courses

The pass rates for certain higher education qualifications were strongly influenced by students’ academic backgrounds. This was true of general Bachelor’s degrees, University technology diplomas (DUT) and BTSs. Those with general baccalauréats were likely to do better on these courses than their counterparts with technological or vocational baccalauréats. However, the type of baccalauréat held by students had little influence on the pass rate for vocational Bachelor's degrees, which was high: 89.5% of students enrolled obtained their qualification in one year. By contrast, only 45.1 of students on Bachelor’s degree programmes obtained their qualification in 3, 4 or 5 years (2008 cohort). More than 60% of DUT and BTS students obtained their qualification in two years. Five years after enrolling at an STS or for a DUT (2008 cohort), 27% of students originally enrolled at an STS and 63% of those enrolled at DUT had obtained a baccalauréat + 3 or 4 years-level qualification, and a significant proportion of them were still continuing their studies (11% of those originally enrolled at STS and 30% of those enrolled at DUT).

Nearly three quarters of those who were awarded a general Bachelor’s degree in 2012-13 stayed on at university the following year to do a Master’s degree (including Master's in Education). One in two Master's degree students were awarded their degree in two years, and one and ten in three years.

The trajectories of students enrolled on CPGEs in scientific or business subjects showed significant levels of success.

When interviewed during the 6th year following enrolment on CPGE, around 75% of baccalauréat holders who had enrolled in a literary, scientific or business preparatory class in 2008 stated that they intended to continue studying, most on university courses or in schools preparing for a baccalauréat + 5 years level qualification. A little over 20% had been awarded a degree, usually at baccalauréat + 5 years level, and had left education. Finally, less than 5% had left higher education without obtaining a higher education qualification.

In 2014, 45% of young people aged between 25 and 29 held a higher education qualification, compared to an average of 32% in the OECD countries. However, 20% of those leaving higher education had not obtained any qualification (nearly 75,000 young people every year).

Higher education is becoming more accessible to students from all social backgrounds and to women, but there remain significant differences between those from different social backgrounds, as well as between courses

The drive to make higher education more widely accessible continues: in 2014, 60% of those aged between 20 and 24 had attended higher education courses (regardless of whether they graduated), as compared with 33% of those aged between 45 and 49.

This increase was observed among students from all social backgrounds.

78% of those aged 20-24 who came from more privileged backgrounds and whose parents worked as managers or in middle management were studying or had studied at a higher education institution, compared to 58% of those aged between 45 and 49. This increase was slightly higher among those whose parents were manual workers or employees, but from a particularly low starting point: 46% of those aged 20-24 were studying or had studied at higher education institutions, compared with 21% of those aged between 45 and 49.

The two-to-one ratio between the two social groups with regard to access to higher education.

This also holds true for qualifications: on average, over the period 2012-2014, 66% of those whose parents worked as managers or in middle management held a higher education qualification, compared with 30% of those whose parents were manual workers or employees.

Although there was little distinction in terms of social background on technological short courses, such as BTS and DUT, divisions were much more noticeable in the case of universities (excluding IUTs) and Grandes Écoles. 32% of those whose parents worked as managers graduated from a Grande École or university with a baccalauréat + 5 years-level or higher qualification, compared with only 7% of those whose parents were manual workers.

More than half of students (55%) are women. Women make up the vast majority (70%) of those studying Arts or Human Sciences subjects, as well as paramedical and social care courses (84%). However, they are in the minority when it comes to the most selective courses, such as CPGEs and IUTs, and still account for only a very small proportion of students on Science courses. In 2014-15, just over a quarter of students (27%) at engineering schools were women. The proportion of women doing apprenticeships is also low (39%).

Women account for a larger share of the student population and more women hold qualifications than men.

Half of all women who left initial education between 2011 and 2013 had obtained a higher education qualification, compared to only 39% of men. Women with higher education qualifications are more likely to hold a baccalauréat + 5 years-level university qualification, whereas men are more likely to obtain qualifications from specialist schools and short vocational courses (BTS or DUT). The labour market is less favourable for women and their access to employment is slower. They are less likely to have permanent employment contracts and more likely to work part time. More specifically, 3 years after leaving higher education, a quarter of women are employed as managers, compared with more than a third of men.

Over the past 20 years, the number of women working as teacher-researchers has increased. In 2014-15, women held 43.9% of all lecturing positions, but still only accounted for 23.2% of university professors.

In a difficult economic context, a higher education qualification remains an advantage in getting a job and pursuing a career

Those leaving higher education enjoy more favourable conditions in accessing the labour market than other applicants, particularly in times of crisis. A study on the occupational integration of young people with DUTs, vocational Bachelor's degrees and Master’s degrees 30 months after graduation, and analyses of occupational integration after 3 or 5 years of young people leaving the education system have shown that a higher education qualification offers a certain degree of protection against unemployment. Three years after leaving higher education, 24% of leavers who did not graduate were unemployed, which was about a dozen points higher than higher education graduates (13% on average). Occupational integration after 5 years showed a reduction in the difference between these two populations, but was still marked: the level of unemployment among higher education graduates had fallen by 4 points on average, to 9%. The level of unemployment among non-graduates had fallen by 9 points to 15%.

The employment conditions for young people graduating from higher education in 2010 were still highly unequal 5 years later, according to the level of qualification and also the subject area and course specialism. In addition, the 2010 generation of graduates has been affected by the current economic crisis. The rate of permanent employment contracts and civil servants reached a plateau while the rate of open-ended employment contracts only increased due to the rise in self-employment.

Increased funding for R&D against a backdrop of intense global competition

In 2013, France’s gross domestic expenditure on R&D (GERD) totalled €47.5 billion, equivalent to 2.24% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), putting it behind Israel (4.2%), South Korea (4.1%), Japan (3.5%), Germany (2.9%) and the United States (2.7%), but ahead of the United Kingdom (1.6%). GERD is expected to reach €48 billion (2.26% of GDP) in 2014.

The research effort came largely from businesses, which carried out 65% of all R&D conducted in France in 2013, a total amount of €30.8 billion, and financed 59% of this work. Public sector GERD totalled €16.8 billion in 2013, with R&D carried out in large part by dedicated research institutions (55%), as well as higher education institutions (40%). SMEs contributed 17% of GERD, more than half of which was invested in the service sector. Large enterprises, which accounted for 57% of GERD, focused three quarters of their funding on high and medium-high technologies. More than 50% of all intramural BERD went towards six industry groups: ‘Manufacture of motor vehicles’, ‘Manufacture of air and spacecraft and related machinery’, ‘Manufacture of basic pharmaceutical products and pharmaceutical preparations’, 'Specialised scientific and technical activities', ‘Computer-related and information service activities’, 'Manufacture of chemicals and chemical products'. Businesses also devoted a considerable proportion of their intramural BERD to multidisciplinary fields such as new materials, nanotechnology, digital, biotechnology and the environment§chapter 45§.

The government helps businesses in their research effort by means of direct funding, collaborations with dedicated civil or military state research institutions and tax incentives such as the R&D tax credit (CIR) and ‘young innovative company’ (YIC) status.

In 2013, 8% of all business R&D was government-funded and the amount of CIR paid out (for R&D, innovation and collections) totalled €5.7 billion. In this regard, France is no different from other OECD countries, where tax incentives are increasingly being used to promote R&D in the private sector, reflecting the more intense competition between different countries when it comes to attracting firms’ R&D divisions. Local authorities also contribute to the research effort, often by financing property transactions and technology transfers. The 2014 research and technology transfer (R&T) budget for local authorities was estimated to be €1.3 billion.

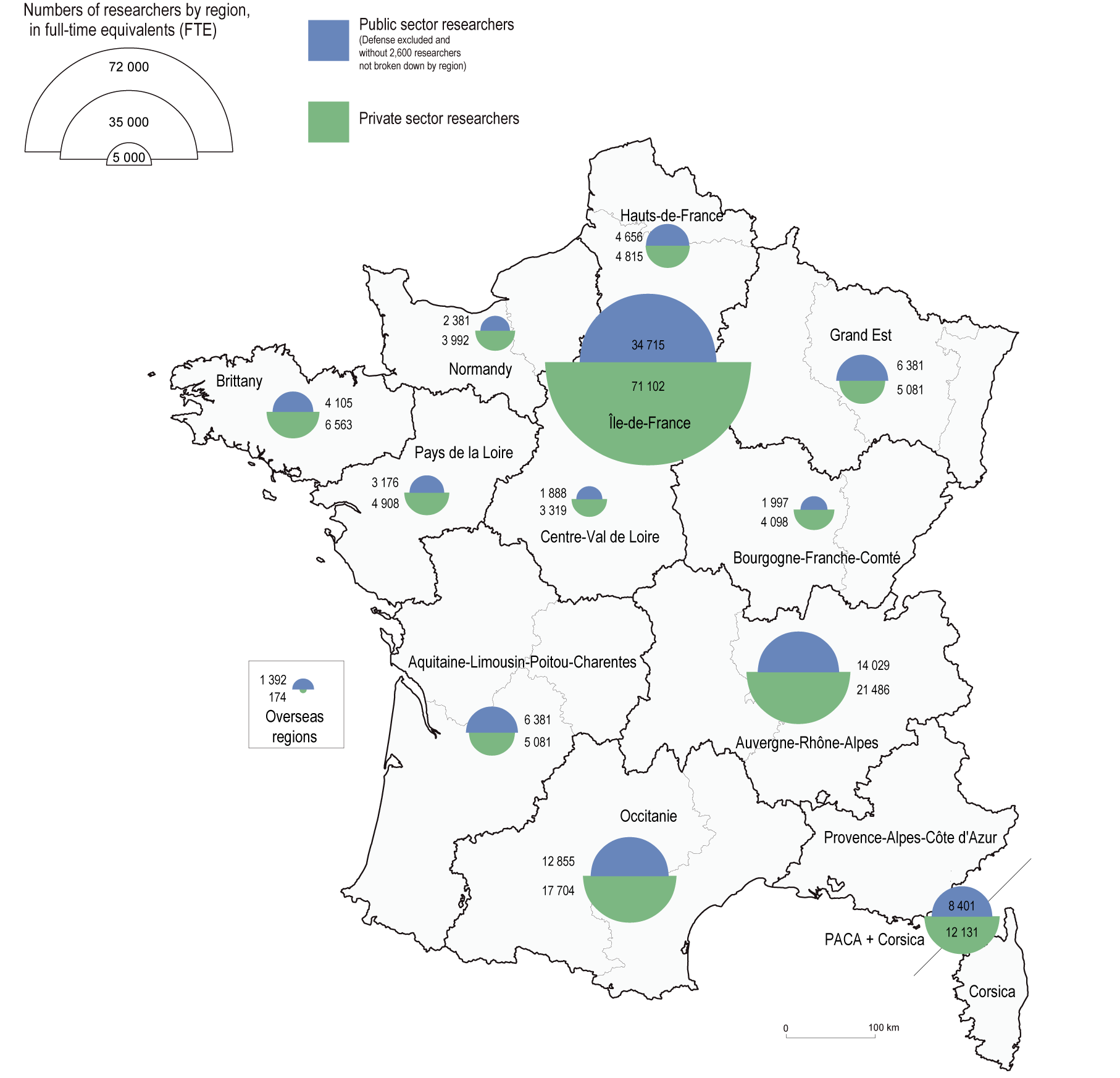

In 2013, nearly 575,300 people, encompassing researchers and supporting staff, were involved in R&D-related activities in some capacity, accounting for just over 418,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) positions. The number of researchers rose sharply between 2008 and 2013 (+ 16.9%) to 266,200 FTE researchers (8,000 more FTE positions than in 2012). This increase was more marked among businesses (+ 26%) than in government (+ 5%). In 2013, 61% of researchers worked for businesses. In the business enterprise sector, nearly half of all researchers worked in just 5 industry groups: ‘Computer-related and information service activities’, ‘Manufacture of motor vehicles’, ‘Specialised scientific and technical activities’, ‘Manufacture of air and spacecraft and related machinery’ and ‘Manufacture of instruments and appliances for measuring, testing and navigation; watches and clocks'. The increase in the number of R&D personnel was largely driven by the service sector, where the number of people working in R&D rose 7 times more quickly than in the industrial sector. If we compare the number of researchers against the active population, France had 9.3 researchers for every 1,000 working people in 2013, fewer than South Korea and Japan, but more than Germany, the United States and the United Kingdom.

The proportion of women working in R&D was 30% in 2013 and was lower in the business enterprise sector (22%) than in government (40%). The proportion of women working as researchers (26%) was also lower than that of women working as supporting staff (36%). An engineering diploma was the most advanced qualification held by more than half of all researchers working in the business enterprise sector in 2013, while only 12% of researchers in this sector held a PhD. In addition to this, 30% of the PhD graduates working in the business enterprise sector also held an engineering diploma.

Scientific publications and patent registrations are two key measurable indicators that can be used to assess a country’s R&D activities. International competition in these two areas is fierce.

In 2014, France was ranked 6th in the world in terms of its share of worldwide scientific publications, which reached 3.3%. Its share of citations after two years in later publications (which reflects their impact on scientific advancement more effectively than simply measuring the number of publications produced) was 3.75%. These two shares have been in decline since 2001, due in large part to the arrival of new countries on the global scientific scene, such as China, India and Brazil. This decline can also be observed among France’s major European counterparts. While their share of publications is falling, their impact indexes are increasing and exceed the global average. The breakdown of French publications by subject area is generally balanced compared with other countries, although it does reveal a marked specialisation in Mathematics.

France is also well-placed internationally as regards patents. In 2013, France was ranked 4th in the world in the European patent system, with 6.3% of applications recorded, and 7th in the world in the United States system, with 2.1% of patents granted. Its specialist fields include ‘Transport’, ‘Micro-structural and g-technology’, ‘Organic fine chemistry’ and ‘Pharmaceuticals’.

France’s share of worldwide patents has been in decline in both systems since the mid-2000s due to the emergence of new countries such as China and South Korea.

France received 11.1% of the financial contribution allocated by the European Union for the Horizon 2020 programme, making it the third largest beneficiary behind Germany and the United Kingdom. Compared to 2013 alone, France's position has increased by around 1.5 points, but is still a cause for concern when its contribution to the European budget (16.3%) and the share of H2020 subsidies that it receives (11.1%) are compared.

How to cite this paper :

close

01 Students enrolled in higher education in the 2014-15 academic year

You can embed this map to your website or your blog by copying the HTML code and pasting it into the source code of your website / blog:

close

02 Numbers of researchers in 2013

You can embed this map to your website or your blog by copying the HTML code and pasting it into the source code of your website / blog:

close

Translation

Etat de l'enseignement supérieur et de la rechercheL'état de l'Enseignement supérieur et de la Recherche en France n°9 - Juin 2016

Etat de l'enseignement supérieur et de la rechercheL'état de l'Enseignement supérieur et de la Recherche en France n°9 - Juin 2016l'état de l'Enseignement supérieur et de la recherche - résumé - Emmanuel Weisenburger